Follow-Up Study Compares Family Food Culture in Three Countries

Learning Life’s Director, Paul Lachelier, plus medical student Anudeep Alberts, Dr. Melissa See and Dr. Kim Bullock of the Georgetown University School of Medicine (GUSM) co-presented a joint study of the food culture of lower-income families in three countries on Monday this week at the Health Literacy Annual Research Conference (HARC) in Bethesda, Maryland.

The cross-national study is a follow-up to research conducted by Drs. Lachelier and See earlier this year. The two studies are intended to better understand the food culture (i.e., shopping, cooking and eating practices, and the meanings attached to those practices) of selected families participating in Learning Life’s Family Diplomacy Initiative (FDI) in Washington DC, San Salvador, El Salvador, and Dakar, Senegal, with an eye to improving their health outcomes in the long-term.

The cross-national study is a follow-up to research conducted by Drs. Lachelier and See earlier this year. The two studies are intended to better understand the food culture (i.e., shopping, cooking and eating practices, and the meanings attached to those practices) of selected families participating in Learning Life’s Family Diplomacy Initiative (FDI) in Washington DC, San Salvador, El Salvador, and Dakar, Senegal, with an eye to improving their health outcomes in the long-term.

Since Fall 2017, Learning Life has been collaborating with GUSM’s Community Health Division on international research and programming, including our food culture project, and more recently our project-supporting family “cook, eat and learn sessions” or CELS. Starting with that food culture project launched this year, Learning Life is grounding its FDI family-to-family projects in health. As Lachelier explains, “the vigor and happiness of individuals, families, communities, societies, indeed the entire world depends on good health. In turn, human health is also impacted by a myriad of factors, from the local food supply to global climate change. This makes health a vital, rich and flexible way for our families to learn about the wider world.” (Click here for more about FDI’s turn to health.)

Since May, GUSM medical student, Anudeep Alberts, among other things worked diligently with Lachelier on the data collection then writing for this research poster. “We look forward to more collaboration with Learning Life on its innovative Citizen Diplomacy Initiative,” said Bullock, who directs GUSM’s Community Health Division. The poster is featured here, and below is the poster’s full text in larger print for readability. For a PDF copy of the poster, contact us at email@learninglife.info.

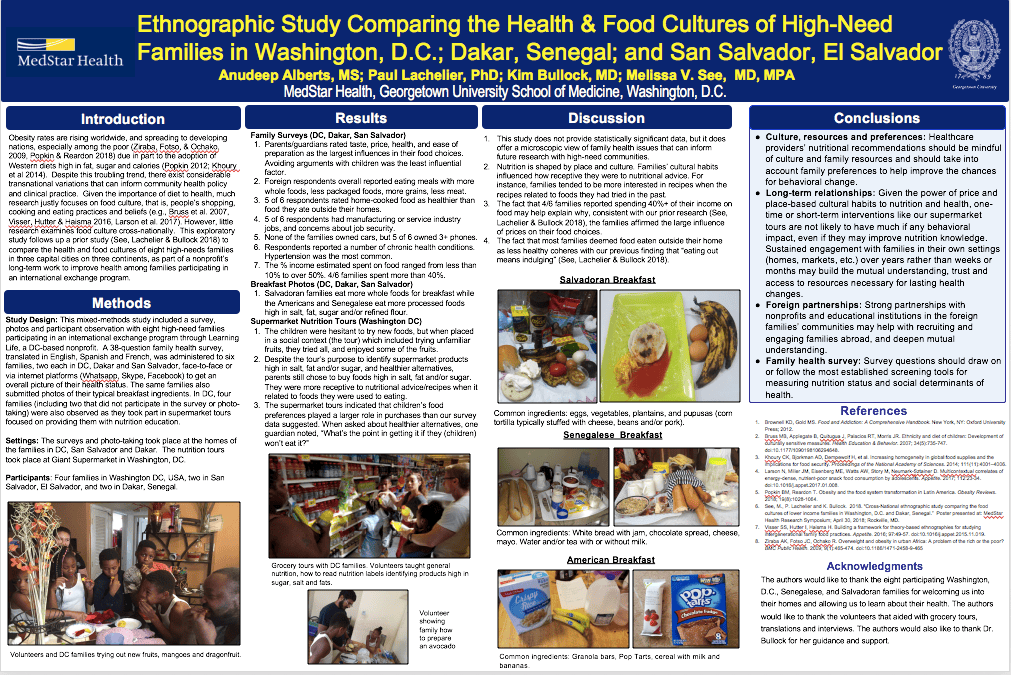

Ethnographic Study Comparing the Health & Food Cultures of High-Need Families in Three Countries

Introduction

Obesity rates are rising worldwide, and spreading to developing nations, especially among the poor (Ziraba, Fotso, & Ochako, 2009, Popkin & Reardon 2018) due in part to the adoption of Western diets high in fat, sugar and calories (Popkin 2012; Khoury et al 2014). Despite this troubling trend, there exist considerable transnational variations that can inform community health policy and clinical practice. Given the importance of diet to health, much research justly focuses on food culture, that is, people’s shopping, cooking and eating practices and beliefs (e.g., Bruss et al. 2007, Visser, Hutter & Haisma 2016, Larson et al. 2017). However, little research examines food culture cross-nationally. This exploratory study follows up a prior study (See, Lachelier & Bullock 2018) to compare the health and food cultures of eight high-needs families in three capital cities on three continents, as part of a nonprofit’s long-term work to improve health among families participating in an international exchange program.

Methods

Study Design: This mixed-methods study included a survey, photos and participant observation with eight high-need families participating in an international exchange program through Learning Life, a DC-based nonprofit. A 38-question family health survey, translated in English, Spanish and French, was administered to six families, two each in DC, Dakar and San Salvador, face-to-face or via internet platforms (Whatsapp, Skype, Facebook) to get an overall picture of their health status. The same families also submitted photos of their typical breakfast ingredients. In DC, four families (including two that did not participate in the survey or photo-taking) were also observed as they took part in supermarket tours focused on providing them with nutrition education.

Settings: The surveys and photo-taking took place at the homes of the families in DC, San Salvador and Dakar. The nutrition tours took place at Giant Supermarket in Washington, DC.

Participants: Four families in Washington DC, USA, two in San Salvador, El Salvador, and two in Dakar, Senegal.

Results

Family Surveys (DC, Dakar, San Salvador)

1.Parents/guardians rated taste, price, health, and ease of preparation as the largest influences in their food choices. Avoiding arguments with children was the least influential factor.

2.Foreign respondents overall reported eating meals with more whole foods, less packaged foods, more grains, less meat.

3.5 of 6 respondents rated home-cooked food as healthier than food they ate outside their homes.

4.5 of 6 respondents had manufacturing or service industry jobs, and concerns about job security.

5.None of the families owned cars, but 5 of 6 owned 3+ phones.

6.Respondents reported a number of chronic health conditions. Hypertension was the most common.

7.The % income estimated spent on food ranged from less than 10% to over 50%. 4/6 families spent more than 40%.

Breakfast Photos (DC, Dakar, San Salvador)

1.Salvadoran families eat more whole foods for breakfast while the Americans and Senegalese eat more processed foods high in salt, fat, sugar and/or refined flour.

Supermarket Nutrition Tours (Washington DC)

1.The children were hesitant to try new foods, but when placed in a social context (the tour) which included trying unfamiliar fruits, they tried all, and enjoyed some of the fruits.

2.Despite the tour’s purpose to identify supermarket products high in salt, fat and/or sugar, and healthier alternatives, parents still chose to buy foods high in salt, fat and/or sugar. They were more receptive to nutritional advice/recipes when it related to foods they were used to eating.

3.The supermarket tours indicated that children’s food preferences played a larger role in purchases than our survey data suggested. When asked about healthier alternatives, one guardian noted, “What’s the point in getting it if they (children) won’t eat it?”

Discussion

1.This study does not provide statistically significant data, but it does offer a microscopic view of family health issues that can inform future research with high-need communities.

2.Nutrition is shaped by place and culture. Families’ cultural habits influenced how receptive they were to nutritional advice. For instance, families tended to be more interested in recipes when the recipes related to foods they had tried in the past.

3.The fact that 4/6 families reported spending 40%+ of their income on food may help explain why, consistent with our prior research (See, Lachelier & Bullock 2018), the families affirmed the large influence of prices on their food choices.

4.The fact that most families deemed food eaten outside their home as less healthy coheres with our previous finding that “eating out means indulging” (See, Lachelier & Bullock 2018).

Conclusions

Culture, resources and preferences: Healthcare providers’ nutritional recommendations should be mindful of culture and family resources and should take into account family preferences to help improve the chances for behavioral change.

Long-term relationships: Given the power of price and place-based cultural habits to nutrition and health, one-time or short-term interventions like our supermarket tours are not likely to have much if any behavioral impact, even if they may improve nutrition knowledge. Sustained engagement with families in their own settings (homes, markets, etc.) over years rather than weeks or months may build the mutual understanding, trust and access to resources necessary for lasting health changes.

Foreign partnerships: Strong partnerships with nonprofits and educational institutions in the foreign families’ communities may help with recruiting and engaging families abroad, and deepen mutual understanding.

Family health survey: Survey questions should draw on or follow the most established screening tools for measuring nutrition status and social determinants of health.

References

1.Brownell KD, Gold MS. Food and Addiction: A Comprehensive Handbook. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 2012.

2.Bruss MB, Applegate B, Quitugua J, Palacios RT, Morris JR. Ethnicity and diet of children: Development of culturally sensitive measures. Health Education & Behavior. 2007; 34(5):735-747. doi:10.1177/1090198106294648.

3.Khoury CK, Bjorkman AD, Dempewolf H, et al. Increasing homogeneity in global food supplies and the implications for food security. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2014; 111(11):4001–4006.

4.Larson N, Miller JM, Eisenberg ME, Watts AW, Story M, Neumark-Sztainer D. Multicontextual correlates of energy-dense, nutrient-poor snack food consumption by adolescents. Appetite. 2017; 112:23-34. doi:10.1016/j.appet.2017.01.008.

5.Popkin BM, Reardon T. Obesity and the food system transformation in Latin America. Obesity Reviews. 2018; 19(8):1028-1064.

6.See, M., P. Lachelier and K. Bullock. 2018. “Cross-National ethnographic study comparing the food cultures of lower income families in Washington, D.C. and Dakar, Senegal.” Poster presented at: MedStar Health Research Symposium; April 30, 2018; Rockville, MD.

7.Visser SS, Hutter I, Haisma H. Building a framework for theory-based ethnographies for studying intergenerational family food practices. Appetite. 2016; 97:49-57. doi:10.1016/j.appet.2015.11.019.

8.Ziraba AK, Fotso JC, Ochako R. Overweight and obesity in urban Africa: A problem of the rich or the poor? BMC Public Health. 2009; 9(1):465-474. doi:10.1186/1471-2458-9-465.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the eight participating Washington, D.C., Senegalese, and Salvadoran families for welcoming us into their homes and allowing us to learn about their health. The authors would like to thank the volunteers that aided with grocery tours, translations and interviews. The authors would also like to thank Dr. Bullock for her guidance and support.